Moving is always difficult. Yet people move all the time, for countless reasons. Sometimes we need to move to be closer to family or friends, or because we want a change of scenery. Many people would prefer to live nearer to nature and green spaces than reside in cramped and busy cities. However, for a proportion of movers their decision to up sticks and relocate is motivated by one thing: work. Each year, millions of people around the world find employment which will require them to move neighbourhoods, villages or even cities. The process can fill one with feelings of excitement, anxiety or maybe something in between. It is nevertheless a gradual process which rarely occurs overnight. Indeed, numerous steps are usually involved and these often concern more than just the person who is moving.

First, one needs to have found a place to live elsewhere. Somewhere located close to nearby amenities, supermarkets, post offices etc. It needs to be somewhere safe, where the mover’s life will not be endangered. After all, where you live is supposed to feel secure, a sanctuary, it is supposed to feel ‘homely’. This initial step is further complicated if the relocator has a partner and or children to support. Ideally, the new home would be close to somewhere where the partner could find a new job themselves should they also wish to work. Moreover, any children coming along for the journey will need new schools to go to. Furthermore, colleagues and supervisors at work must be notified of the move, as do local friends and family. Thus, from the very start of the process, other people, usually multiple, must be brought into the mix.

Handling it all is hard work, but with the right support and understanding it can be managed. Imagine then, how much harder this process becomes when one is moving to another country for work. This is the reality for many in the diplomatic sector, who often find themselves representing their countries abroad, hundreds if not thousands of kilometres away from everything and everyone they know. For these diplomats, having some kind of support from their national diplomatic service to manage this transition, for themselves and for any family they must take with them, is absolutely vital.

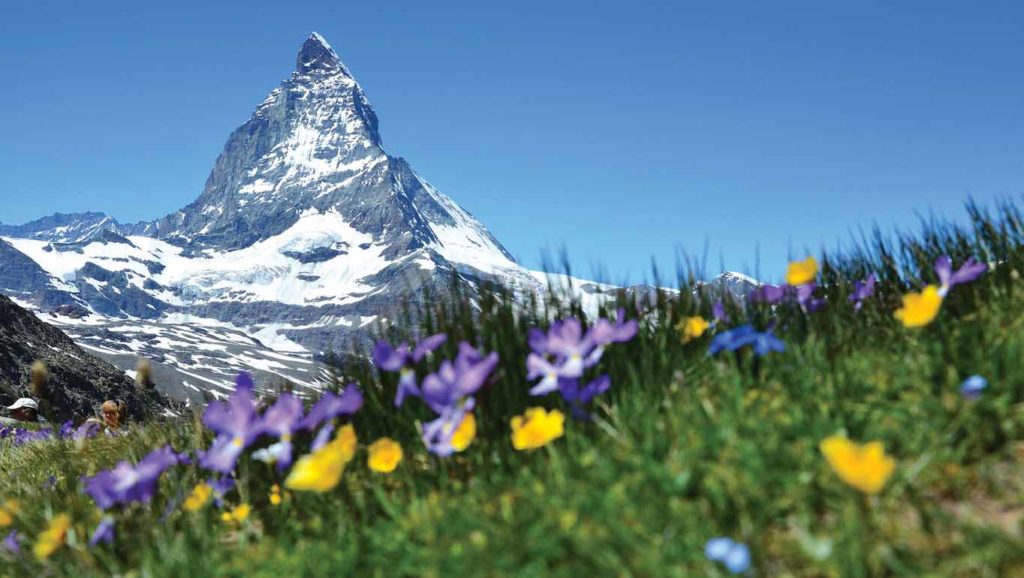

Switzerland, with the United Nations on its very doorstep in Geneva, has established itself as a nexus of global diplomacy. It therefore seemed like a good place to start when investigating the mobility of diplomats in one of the world’s most diplomacy-friendly countries. In an interview on the subject, UN Today had the opportunity to speak with Mrs. Andrea Rauber Saxer, Head of Human Resources at the Federal Department of Foreign Affairs of Switzerland (FDFA), to discuss the framework in place for Swiss diplomats when it comes to issues such as staff mobility.

The main pillars of the mobility policy for Swiss diplomats, as well as the length of their mobility cycle, are of great importance, as Mrs. Rauber Saxer explains: “whenever a diplomat is transferred from one duty station to another, the FDFA primarily ensures that there is the best possible match between the requirements of a position and the skills and experience of the applicant. The competencies and potential of our civil servants are at the centre of the career system. As a rule, the period of employment in a position is four years for transferable staff (ie. staff subject to mobility rules). This applies to both junior and senior staff. In difficult or very difficult contexts, staff members can apply for a reduction to 3 or 2 years. In exceptional cases, e.g. shortly before retirement, they can apply for an extension to 5 years”.

And what about whether the policy accommodates diplomats who have special constraints such as family or medical constraints? Mrs. Rauber Saxer highlights that: “wherever possible, personal aspects such as family circumstances, partners and marital status, nationality, career aspirations (including dual career), children and their schooling needs – or specific health aspects are taken into account in the transfer process. There are a few countries that are categorized as not family duty stations. Transferable employees must apply for at least three vacant posts. At least one of these posts must be in a difficult context. Difficult context means the post is in a country with a low ‘quality of living’ index. The FDFA tries to alternate between assignments abroad (in difficult and less difficult contexts) and assignments in Switzerland”.

Finally, what about distinguishing between female and male diplomats, and how do promotions work? Mrs. Rauber Saxer informs us that: “the FDFA pursues an equal opportunities policy and offers diplomats equal opportunities and possibilities regardless of their gender. The FDFA has a salary system based on functions. This means that each position is classified according to the level of responsibilities and requirements and depending on required competencies. This system aims at remunerating staff depending on their effective role and responsibilities rather than according to seniority, thus allowing younger ‘high potential’ staff to move up the ladder more quickly. A transfer to a higher-ranking position could be understood as a promotion; however, the FDFA has abolished the promotion system as part of a personnel reform in 2019 in a deliberate move away from conventional career thinking, which is no longer up-to-date and not agile enough. If staff are transferred to a lower-ranking position, they have a so-called vested right to their previous salary until the next transfer. This cultural change should also lead to employees taking personal responsibility for their professional development (aka ‘lifelong learning’).

Swiss diplomacy’s emphasis on equality of opportunity, sensible posting periods and consideration of a diplomat’s personal circumstances therefore points to a diplomatic sector which is highly conscious of easing any restrictions on mobility one may encounter. Moreover, Switzerland’s system of tiering postings by difficulty and emphasis on learning and personal development identifies a need to keep fairness and educational enrichment as a core component of its modern diplomacy. A system which takes these factors into account can have a lasting positive impact on its workforce and should, ultimately, be normalised elsewhere”.