The first chilling lines in the epilogue to Ainda estou aqui (I’m still here), winner of this year’s Oscar for Best International Film sets the scene for the tumultuous events that unfold in the film: “In 2014, five officers from the 1st Division of the Brazilian army were accused of torturing and murdering Rubens Beyrodt Paiva between 21 and 22 January 1971. To date, nobody has been arrested or punished.”

The story of former Congressman Paiva’s family starts brightly as his children play carefree on the golden sands of the Cidade Maravilhosa and he entertains friends with music, dancing and good food. The whole family is suddenly plunged into darkness when their beachfront Rio de Janeiro home is invaded by a group of plain clothed and unidentified men, who patiently wait for Paiva to change into a jacket and tie before accompanying him in his car to an unknown destination for questioning. His wife Eunice and 15 year-old daughter Eliana soon experience the same fate, although in their case, they are forced to put hoods over their heads, so that they do not know where they are being taken. Eliana is released the following day and left in another part of Rio, whilst Eunice is held in incommunicado detention for almost two weeks.

The film then centers on Eunice’s attempts to obtain information about her husband’s whereabouts, while at the same time trying to shield her five children from the realization that they may never see their father again. Paiva’s story is one which is shared by hundreds of others, who were forcibly taken during the military dictatorship which ruled Brazil between 1964 and 1985. As we see in the film, the authorities refused to acknowledge that they had detained and were secretly holding these political opponents, causing the material deprivation and constant psychological torture of their loved ones, who hope against hope, as Eunice tells the press when she finally obtains a death certificate for her husband, 25 years later in 1996.

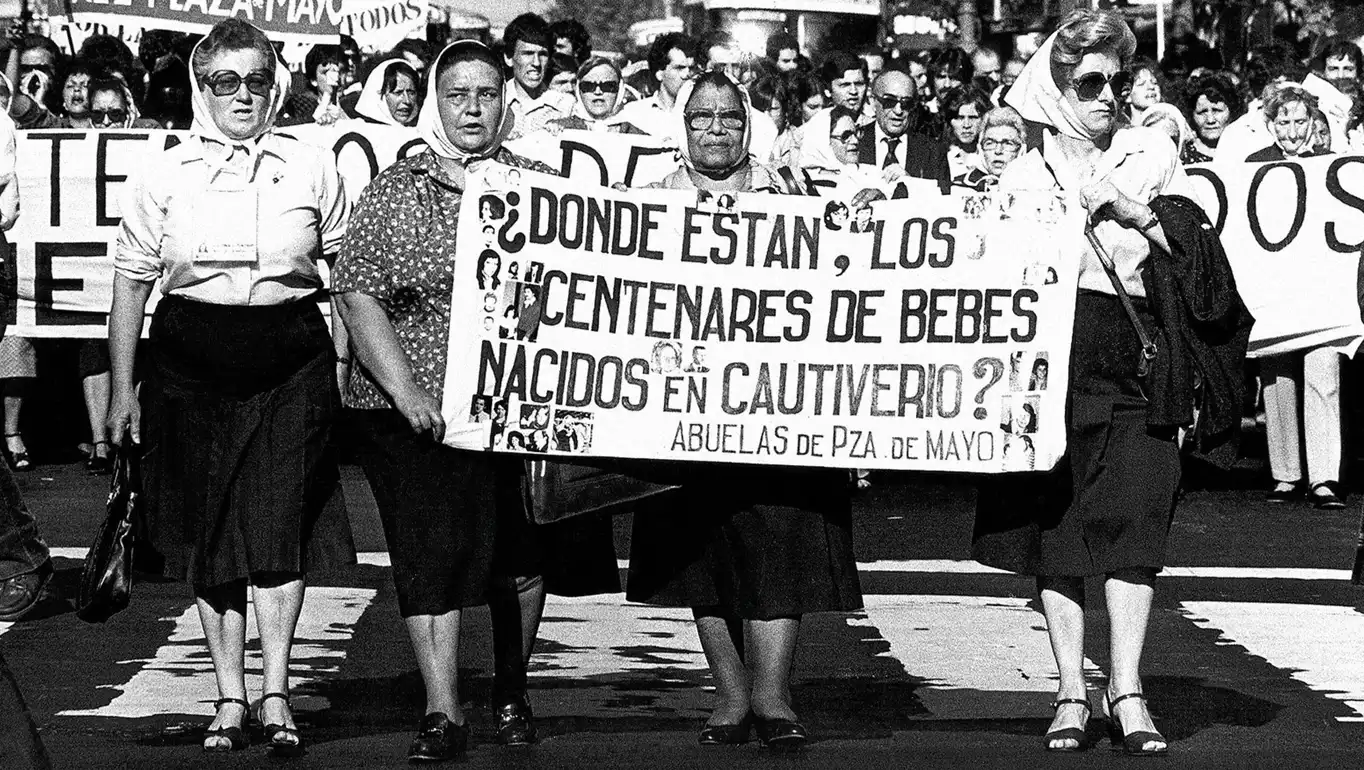

Enforced disappearance was a weapon widely used by a number of Latin American dictatorships to silence and instill fear in dissidents. Wives and mothers in particular, but also husbands, brothers and subsequently children, banded together in their desperate searches for victims. Pressure from civil society, was perhaps most visible in the protests of the Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo. This was organized by and consisted of Argentinian grandmothers searching for their children and grandchildren abducted by the Argentinian military or born in secret detention following their mothers’ disappearance and handed over to families with military ties in the late 70’s and early 80’s. These protests were a determining factor in achieving the 1992 United Nations Declaration on the Protection of all Persons from Enforced Disappearance (GA Resolution 47/133). Thereafter, the adoption of the International Convention for the Protection of all Persons from Enforced Disappearance (ICPPED) in 2006 was another milestone in preventing further abductions.

The Convention, with 76 ratifications to date, is the most recent of the core Human Rights treaties and contains a number of innovative features. This includes the definition of Enforced Disappearance as a continuous crime, which does not cease until the fate or whereabouts of the direct victims become known.

Furthermore, the concept of victims also encompasses the indirect victims, family members and loved ones, who suffer years of trauma described by Paiva’s widow in the film. According to Article 24, they have the right to reparations for material and moral damages, such as satisfaction, which includes the restoration of dignity and reputation. The Brazilian state, which is a party to the Convention, has taken important steps in this direction by establishing commissions of inquiry, namely the Truth Commission and the Special Commission on Political Deaths and Disappearances, which recently adopted a law to enable death certificates. This law allowed the reversal from the victims’ original cause of death from ‘natural causes’ to be amended and re-issued with the reference “death through State violence in the context of political persecution during the military dictatorship,” as explained by the Minister of Human Rights and Citizenship, H.E. Macaé Evaristo, during the recent high-level segment of the Human Rights Council.

Yet, for the Paivas, there are still two important obstacles before closure can be brought: impunity for the perpetrators and a dignified burial for the victim. For many families, given the length of time that has lapsed since the disappearance, this is often all they can hope for. Many victims associations though, from Mexico to Syria, the Philippines and beyond, are desperately digging with shovels and even their bare hands, as they try to find and then identify the human remains buried in clandestine, mass graves.

As a result of their past, certain countries, including Argentina and Guatemala, have accumulated considerable know-how in forensic anthropology and make their expertise available to others who are now confronting the painful aftermath of conflict and oppressive regimes. Meanwhile, taking DNA samples from family members to build genetic databases will greatly accelerate identification procedures. In turn, this will hopefully increase the currently low number of successful identifications. After all, time is of the essence, as parents and grandparents grow older.

While the Committee of Experts established under the ICPPED monitors and supports states party in meeting their obligations regarding disappearances that occurred decades ago, it also has an urgent actions procedure for engaging with states on the new cases still emerging on an increasing and alarming scale in various parts of the world (allegations, in fact, concern over a third of states party). One need look no further than Syria, where human rights organizations estimate that between 100 and 150,000 people went missing over the past 14 years, many of them disappeared by or with the acquiescence of the state security apparatus.

For its part, the United Nations Working Group on Enforced and Involuntary Disappearances (established by a Human Rights Council resolution and whose mandate enables it consider cases from any country and not just States party to the Convention), has transmitted 150 new allegations of enforced disappearance, to the respective governments of the countries concerned. This group examines over 600 continuing cases at each of its three annual sessions.

New and more complex trends are emerging, making prevention and eradication of this horrific practice more challenging. Not only is enforced disappearance being used as a weapon by a range of non-State actors, such as armed insurgents like the Rapid Support Forces in Sudan and drug cartels, but different groups are also being targeted. Examples of this include indigenous land and environmental human rights defenders. Furthermore, more disappearances are occurring in the context of migration. This is because migrants fall into the clutches of smugglers and human traffickers, and in conflict areas, with victims being taken across international borders by their captors.

In such contexts, ratification of the International Convention assumes ever greater importance, as States accept international obligations to ensure that the rule of law always prevails and that there is no impunity for this crime against humanity. Perpetrators are being held to account under criminal law, regardless of their rank or status, and punished with appropriate sentences. Even though victims often convert their grieving into energy, just as Eunice Paiva did in her decades-long quest for truth, political will, resources, institutional response and corollaries of accession to the Convention are of the essence.