One of the greatest privileges of a UN career is the opportunity to work with remarkable colleagues and partners.

Looking back on some wonderful assignments, this was, for me, the highlight of my own UN experience.

To begin on a lighter note: as Chef de Cabinet to the talented UNOG Director-General Jan Martenson, he would gleefully inform me before breakfast how he had already landed me in trouble. Before coming to the Palais, he had written detective novels (very popular in his native Sweden) which were often mischievously inspired by his UN team.

As a very young Chef de Cabinet, I also recall the great Kofi Annan, then head of UN Human Resources, reminding me to be more deferential and polite to the venerable UN Ambassadors.

Later in Geneva, and more seriously, working as Chef de Cabinet to Sadruddin Aga Khan, I was introduced to a world of luminaries beyond my limited experience. Sadruddin led UN humanitarian operations in the aftermath of the first Gulf War; our negotiating partner was Deputy Prime Minister Tariq Aziz, who would depart after dinner for the Palace to receive instructions from Saddam Hussein for the next day’s meetings. Like many others who knew him, I saw Sadruddin as a visionary leader who would have made an exceptional Secretary-General.

Another Swedish UN leader, Jan Eliasson, impressed me during my time supporting him in the newly created Department of Humanitarian Affairs. His staunch commitment to the principle of humanitarian intervention, the “droit d’ingérence,” culminating in R2P—was matched by his diplomatic skill in shepherding the landmark General Assembly Resolution 46/182, which laid the foundation for all future UN humanitarian endeavors.

Working for several years with Secretary-General Javier Pérez de Cuéllar, I saw him as the consummate diplomat, deploying equal measures of charm and intelligence to pursue UN solutions to intractable conflicts. At his side, I experienced unforgettable moments: meeting leaders from Indira Gandhi to Olof Palme in informal settings; listening to Margaret Thatcher at 10 Downing Street berating her own Foreign Secretary for not taking a tougher line on the Falklands/Malvinas; watching President George H. W. Bush poring over a map of the Middle East on the floor of the Secretary-General’s office; and being greeted on the steps of Beijing’s Great Hall of the People by a short, smiling figure I suddenly realized was Deng Xiaoping—who then regaled us with anecdotes from his extraordinary life. All these encounters were managed by Pérez de Cuéllar, with his customary tact and aplomb.

While working with Pérez de Cuéllar, I also found my literary studies were not in vain. Writing his speeches, I had him quoting the Irish poet W. B. Yeats before the General Assembly to denounce the nuclear arms race. His remarks made the front page of The New York Times—and drew the ire of some Western Permanent Missions that disapproved of his stance.

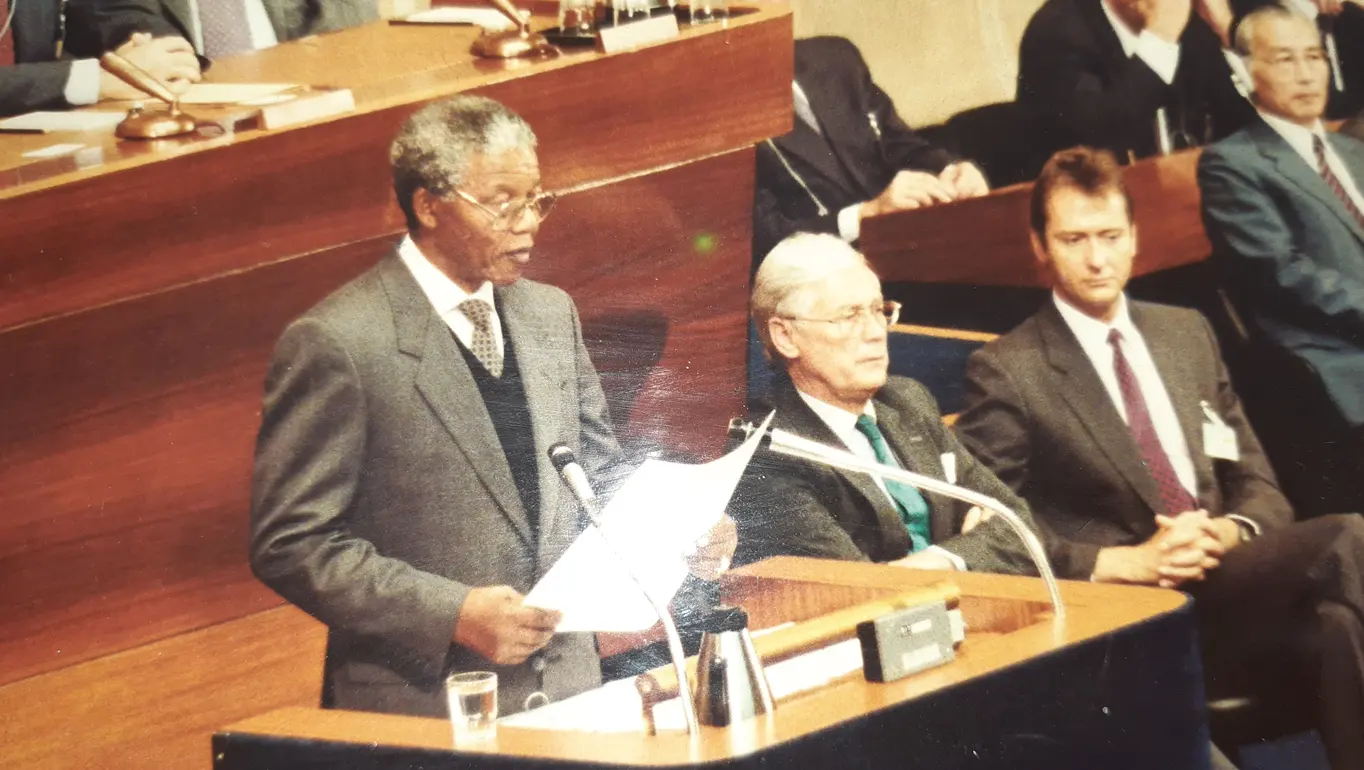

With Jan Martenson at UNOG, we also welcomed our share of world figures—from Nelson Mandela to Lech Wałęsa and Colin Powell—all of whom Jan skillfully made feel that the UN was their home and a supportive environment.

The senior UN officials I was fortunate enough to encounter or work with displayed exemplary diplomatic, cultural, and linguistic skills, often putting my own Oxford education to shame. Those who led the Secretary-General’s Office at various times—Alvaro de Soto, Albert Rohan, Virendra Dayal, Rafi Ahmed, and others—were international figures whose talents overwhelmed me as a young Secretariat officer. I learned from the varied perspectives they brought from their own cultural and political backgrounds, all of which enriched my limited Western European outlook. Yet these leaders embodied and expressed a commitment to the UN’s universal ideals of peace, justice, human dignity, and well-being, transcending national boundaries. Through their example, I came to feel that the UN was not just an institution, but a living reality, a community of hope that brought Charter principles to life.

The UN faces a difficult path today in many of its areas of ambition and responsibility. I now teach on some of its past, present, and future challenges at various universities. My students are often disappointed by the UN’s inability to end current conflicts or resolve global crises. But its ideals and universal values have inspired towering personalities who, in its service, left a lasting mark on humanity’s progress.

To end, I would add that the global figure who left the deepest impression on me during my UN career was Mother Teresa. She asked for our help in flying to Baghdad to care for orphans in the aftermath of the first Gulf War. Driving to Cointrin Airport, we tried to warn her of the perils of meeting Saddam Hussein, and how he might exploit her presence for his own purposes. She replied with a single sentence: “He seems so much in need of love.” We were awed into silence. In that moment, she had expressed the heart of the UN in ways beyond our imagining.