There are growing concerns that robots and artificial intelligence will soon replace humans, hence the role of businesses and governments become crucial to avoid job losses and higher inequality.

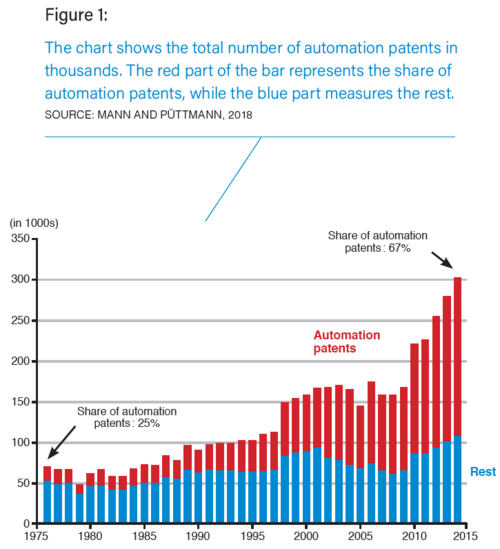

Recent progress in artificial intelligence has been stunning: machines are taking phone calls, understanding questions and suggesting solutions, often much faster and efficiently than humans. The share of automation patents over the total has increased from 25 per cent in 1975 up to 67 per cent in 2015 (see Figure 1).

Will artificial intelligence and robots generate a jobless future?

There are growing concerns that the increased use of various digital technologies will lead to job losses as human work is replaced by robots and artificial intelligence. Many studies have tried to assess the possible job destruction impact of robotisation and artificial intelligence. Among these studies, Frey and Osborne (2017) estimate that 47 per cent of jobs in the United States and 37 per cent in the United Kingdom are at risk of automation. A very similar outlook emerged form a McKinsey study, which estimates that 60 per cent of all occupations can potentially be automised. According to the World Bank (2016), in developing countries an even higher percentage of jobs are at risk. In the same vein, Carbonero et al. (2018) argue that while the employment effects of robotisation are rather small in developed countries, employment losses are much more pronounced in emerging countries and are mostly due to robot-driven reshoring.

What all these studies have in common is that they focus on potential gross job destruction. Nevertheless, so far there is no evidence that job loss is mounting. In the recent years, we have now reasons to believe that artificial intelligence is likely to affect specific tasks and not full occupation, since we have to consider the coexistence of three effects: task-substitution, task-complementarity and creation of new jobs.

In the case of matching applications (e.g. Linkedin, Amazon), existing tasks are being taken over, often in a more efficient way, through algorithms that allow the matching of supply and demand more rapidly and more precisely.

In the case of classification tasks, AI-based applications help workers involved in such tasks but without substituting human workers. An example might be robotic surgery or computer-assisted surgery which allows surgeons to perform surgical intervention remotely. In this case, there is no substitution, but a kind of “cobotisation”, that is a co-working between humans and artificial intelligence.

Finally, as regards process-management tasks, AI-based applications often carry out tasks that no human workforce is capable to perform. Moreover, the digital economy has created new jobs (e.g. AI-programmers, e-commerce specialists, apps and software developers, crowd-workers, influencer and those working on social media).

Keeping this in mind and considering the scarcity of data on artificial intelligence, it is difficult nowadays to predict the overall effect of artificial intelligence on jobs. This is why policies are relevant in order to minimize possible negative effects and make sure that gains from artificial intelligence are equally shared.

Should we expect more inequality?

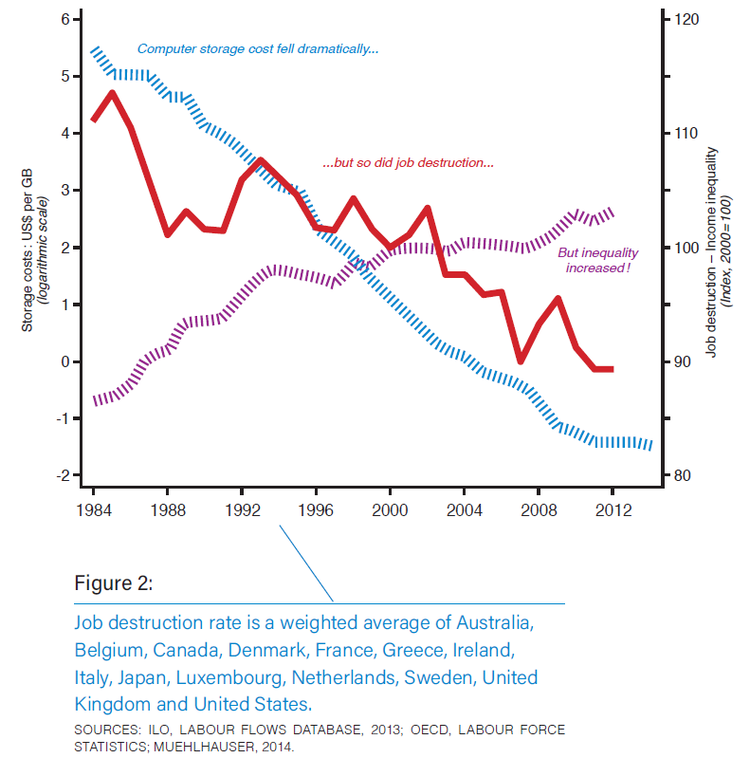

While the evidence is not conclusive with regard to employment lost through digitalization and artificial intelligence, there seems to be clearer evidence concerning the impact on inequality. If we assume that computing costs is an accurate proxy for artificial intelligence – since decreasing computing costs have led to an explosion in installed computing power and storage capacity – we do observe that since mid-1980s automation has not been associated to increasing job destruction, rather than to increasing inequality (see Figure 2).

Technological progress in recent years appears to be resulting in greater inequality and labour market polarization. Automation due to artificial intelligence, robots and computers is likely to affect mostly middle-class job. Entry-level legal services, accounting, logistics and retail will see many tasks replaced by machines which require little oversight or maintenance by employees. Experience suggests that, rather than become unemployed, a growing number of those displaced will compete downwards, leading to further job polarisation. However, according to a recent study by Michael Webb, artificial intelligence, in contrast to software and robots, is directed at high-skilled tasks and hence is expected to have the reverse effect on inequality, since better-educated and better-paid workers will be the most affected by the new AI-based technologies. Still, this study warned that artificial intelligence will reduce 90:10 wage inequality, but will not affect the top 1% earners.

Inequality has increased not only across workers undertaking different tasks in the same firm, but also across firms. According to a recent research conducted at the World Bank, wage inequality is indeed driven by wage gaps across firms, at least in Europe, which are at the same time driven by differences in the rate of adoption of digital technologies. In this era of artificial intelligence, we are witnessing the emergence of a new business model, called “surveillance capitalism”, which is based on collecting data without barriers to access and exploited with proprietary algorithms. While the data come free – and users are often all too willing to give up their privacy – data collection is not since it is protected by intellectual property rights. While on the one side the rise of new “big data” platforms, which are able to collect huge information on consumer behaviours and preferences, certainly enhances the efficiency of the economy, on the other side “big data” have encouraged the emergence of “superstar” firms that are pulling away from the rest of the economy. These “superstars”, mostly digital companies such as Facebook, Google, Amazon and Netflix, concentrate profits and wealth as they collect and exploit vast amounts of data for their algorithms to individualise prices and product offers. The underlying network externalities allow innovative “superstar” firms to first enter the market and gain market power, leaving new entrants little chance to compete for market shares or profits. Not surprisingly, concentrated winner-take-all markets is associated with the fall in the labour share.

What to do for a more inclusive growth?

Inclusive growth and decent work for all workers constitute the social dimension of Sustainable Development Goal 8 (SDG 8) in the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. SDG 8 exhorts the international community to “promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all”. Progress in that dimension is measured in terms of equality, fairness and justice within societies. However, the evidence suggests that most countries still have a long way to go.

In order to prevent an undesirable lose-lose scenario – where technological change comes at the cost of mass unemployment and growing inequality – it is critical that businesses take an active role in supporting their existing workforces through reskilling and upskilling. In addition, governments should implement effective policies to facilitate the transition to the new world of work where humans will co-work with artificial intelligence, without leaving anybody behind. In this light, a necessary step is readapting the current education system to support the transit to new tasks required by AI-based technologies.

Policies are relevant to minimize possible negative effects & ensure gains from artificial intelligence are equally shared.

Moreover, the emergence of these “superstar” firms has raised concerns that some sectors are too concentrated. Although these “superstar” firms may not exercise market power in ways that harm consumers in the short run, policy-makers should ensure that markets remain contestable and competitive. Access to data should hence be shared at little or no cost, so that new entrants can compete. Recently, Ekkehard Ernst discussed several solutions to address potential rise in inequality in the era of “surveillance capitalism”.4 Considering data as a common good which allows the extraction of rents would help restore the balance between individual data suppliers and corporate platform providers. Treating data ownership as a collective-action problem can limit the increases in concentration and market power and will ultimately help to address the continuous rise in inequality.

1 Kelly et al. (2017). 2 See Barkai (2017) and Autor et al. (2017). 3 For more details, we refer the reader to ILO (2019). 4 I refer the reader to “Big Data and its enclosure of the commons”, published in Social Europe on 12 June 2019.