After a long career at the UN, Ute Kollies, former Head of Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), divulges some of her expertise and knowledge about the field, and her career which saw her become Deputy Regional Director for West Africa and Head of Office in Chad. She stayed as Head of Office in Mali – at a time of deep internal strife – until the end of her career.

Please can you tell us about your career at the UN, and what led you there?

I had lived in Zimbabwe for about 13 years when I started applying for new jobs, because I felt I needed to go back to a career in an international organization. I saw an advertisement in the German newspaper ‘Die Zeit’ by the government, inviting people to come and sit the NCE exam (a competitive national exam), as at the time, Germany was underrepresented in the United Nations. I sat the exam alongside about 700 other people in Frankfurt town hall after flying from Zimbabwe, with the aim to become a UN staff member. I think I had an advantage living in an anglophone country and could speak English fluently, as I was invited for the oral assessment in New York nine months later. Out of the 700 of us, only two were selected and I was offered a job to start as a P2 in Geneva in the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) Secretariat. From there, I changed jobs about every three years or so, becoming the Desk Officer (P3) for West Africa, which at the time only covered Liberia, Guinea, and Sierra Leone due to wars going on in that region as of 2002. I became a P4 in the ‘Surge Capacity Section’ in Geneva, but this role also gave me a lot of opportunities to travel on the continent, with extensive missions to other African countries as well as Yemen. I went from covering three to four countries, to becoming Deputy Regional Director for West Africa, opening our office in Senegal.

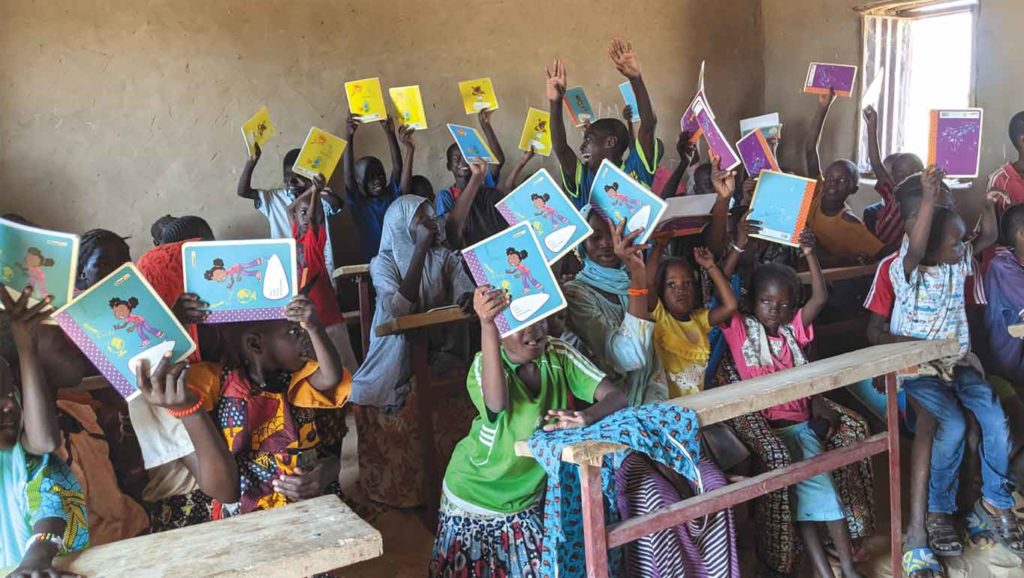

My long experience in Africa led to my becoming Head of Office in Chad, dealing with its own chronic poverty, internal strife and refugee crisis with over 250,000 refugees from Sudan in Eastern Chad. I then transferred to the Ivory Coast for a couple of years to close our office there as Ivory Coast had improved its situation and humanitarian aid was due to scale back while development actors were to take over. I then became Head of Office in Mali, already in conflict following the coup in 2012 and the reignited rebellion, where I stayed for eight years until the end of my career. I progressed from support staff to a managerial position, from HQ to the field , so experienced a range of career highlights and challenges. As a member of a working class family, I have always felt the urge to help people in under-privileged positions. For instance, during my studies I was very involved in the feminist, the so called ‘third world’ and anti-apartheid movements. That gave me the motivation to look to international organizations such as the UN, with its charter, which I think is one of the most important documents we have in the world. Working towards social progress, justice and work to create peace and achieve equality of opportunity were the most motivating factors for me when applying to work for the UN.

As Head of OCHA, what were the greatest barriers facing your mission in addressing humanitarian assistance and protection?

There were many, as you can imagine. I don’t remember a single country where we received the funding we asked for. Humanitarian response plans often ask for an amount of money that is incomparably less to what is being spent for wars and military interventions. We often only offer a ‘plaster’ to a given population’s injury when providing assistance and protection due to underfunding. Humanitarian assistance is a necessary basis for the creation of peace in countries confronted by multi-layered conflicts involving religious, ethnic and class issues as well as the consequences of climate change, demographic challenges and underdevelopment. Although the system receives a lot more money than we did ten years ago, there are more conflicts and more victims to serve so it still doesn’t cover the needs identified. Earmarked and unearmarked funding poses problems as often critical needs of certain groups or certain geographic areas cannot be covered.

The second problem is competition of conflicts. When there is a new conflict that raises higher political interest, money is often redirected. There are currently 55 armed conflicts raging in the world, but many people are not aware of this as the media often only focuses on the one conflict that is of highest interest.

Thirdly, access is a huge problem. I have been in countries where there has been conflict not only between different ethnic groups with militias, but also with so-called terrorist/jihadi forces sometimes blocking off areas to internally displaced people in zones these forces control. Obviously that needs an approach that facilitates access and maintains the adherence to the humanitarian principles, neutrality, independence, impartiality and humanity – no militarization of aid, negotiating access with belligerents who often only want aid to their geographic area, no handing over of aid to non humanitarians for distribution, etc.

Our own security system, UNDSS, in many cases often also poses a challenge and prevents us or makes delivering assistance in highly insecure environments more difficult, even though they are mandated to facilitate humanitarian access.

The lack of actors in highly insecure areas is another problem. Often humanitarian actors retreat to the capital cities, and transfer the risk to local organizations. While I support the localization of humanitarian aid, I personally don’t like only transferring the risk to them as we have often seen that they are just as targeted as we are – if not more. I always tried to lead by example and traveled to these locations many times myself.

How did your methods changed when you took over as Head of OCHA, and did you have to adapt in the ever-changing geopolitical climate?

Throughout my career, a lot changed. We did not have iPhones and social media at the beginning, whereas now we must invest a lot more in social media to reach the public and to provide constant updates for our donors. Reporting to them is unfortunately not standardized and so a lot of effort needs to be put into that. When I first joined, many topics were not yet of importance: accountability, nexus, localization of aid, etc. All these topics need reports and updates, taking valuable time away from the core business: helping people in need. Methods and content have changed, but in my opinion, over-bureaucratization has reached new heights. This detracts from our first mandate which is the delivery of humanitarian assistance and protection. Sometimes you hardly have the time to do your most important work as there is so much reporting to do. A lot of changes have taken place, but not all necessarily for the better.

The conflicts themselves have changed and increased their complexity with causes intertwined such as climate change, demographics, access to land and water, religious issues, geopolitical influence, historical factors, ethnic violence etc. Humanitarian actors need more knowledge in order to deal with the realities on the ground.

Positive tools have also emerged such as the CERF (Central Emergency Revolving Fund) and the Country-Based Pooled Funds, which give us more flexibility and a quicker response option under the leadership of the humanitarian coordinator.

What lessons have you learned throughout your career?

We need more sustainability in humanitarian assistance. Distribution of aid can stabilize populations in the short-term but does not lead to long-term development and return to self-reliance of the victims. The nexus approach was a theoretical start that needed further practical development at the time.

We must raise more funding without expending more money on fundraising. We also need to reduce overhead costs that often multiply as monies received are partially transferred to second and third partners, who also claim overhead costs.

I also think we should make more of an effort to recruit female staff, and local staff with national and regional language skills. In many meetings I have been the only woman in the room, especially in offices outside the capital city. Many women victims of war do not talk to male members of staff about sensitive topics, due to taboos and cultural restrictions – which is why we need more women staff.

We need to increase prevention, which is often better than ‘cure’, but funding is hard to receive. In natural and environmental (and some conflict) disasters, prevention money to address underlying problems would limit the scale of the problem. Whilst I felt privileged to be a UN staff member, I think the organization needs to reform and be strengthened. The issue of equality of representation in the Security Council needs to be addressed, where political solutions are occasionally blocked and continents like Africa, South America and Asia are not or not appropriately represented.

What advice would you give to young humanitarians?

I now teach from time to time at universities, and so I meet a lot of young humanitarians, some of whom are refugees studying in Europe. I recommend that students, after having acquired a basis in all spheres of humanitarian assistance and protection, specialize in a topic, which they are passionate about and are constantly motivated by. Internships in international organizations, NGOs or Think Tanks are helpful to get some practical insights. I think the UN as a whole should pay interns (I know some UN organizations do that already) to make it possible for students from all backgrounds to become interns.

Networking is also important beyond LinkedIn, as you need to have relations and personal connections with people who have already experience in the field or in organizations of interest. It is important to speak at least two UN languages fluently in order to be able to function in the field. Mentors in the system are useful as they can tell you what it means to work for the organization. I have been a mentor a few times and my mentees found it very useful.

Humanitarians have to be courageous and persistent, as there is always a minimum risk involved in our work. Wherever you are in the field you need passion and courage to work in conflict zones, as you are risking your life and sometimes your well-being. Reduce and resist bureaucracy as much as you can, as the people in need require your time and full attention.