Did you know that the UN General Assembly (UNGA) has declared an International Day of Neutrality? Introduced by Turkmenistan, Resolution 71/275 of 2017 declares 12 December the International Day of Neutrality – and invites all Member States to mark its observance. More substantively, it suggests that the Secretary-General should continue to cooperate closely with neutral states, with a view to implementing the principles of preventive diplomacy while using those principles in their mediation activities (all only with voluntary contributions, of course!).

So what does neutrality really mean in 2021? No doubt everyone’s thoughts will first turn to Switzerland, the state most unequivocally committed to a permanent armed neutrality, and to Geneva, the seat of the International Red Cross and home to UNOG, as well as numerous UN programmes and agencies. Swiss neutrality formally dates back to the Congress of Vienna in 1815, and Switzerland has long prided itself on its good offices and its role as a protecting power or a mediator. For the Red Cross, its base in neutral Switzerland reinforces its impartiality and hence its efficacy in caring for victims of conflict.

However, neutrality, even in Switzerland, is not a static concept. When I was Chef de Cabinet at UNOG – quite a while ago – the Swiss electorate dismayed us by voting by a margin of three to one not to join the UN. That was in 1986 and one of the key reasons adduced was that UN membership would jeopardise Swiss neutrality. Even in Geneva, 70% were against joining. And yet, 15 years later in another referendum, the Swiss electorate decided – in a close vote – to join the UN. Apparently, it was no longer felt that UN membership was incompatible with neutrality. And now, Switzerland is set to join the Security Council next year as non-permanent Member. It would take a much longer article than this to analyse the changing motivations behind these diverse positions, but it’s clearly not possible to point to a hard and fast definition of neutrality beyond the basic premise of ‘not taking sides in a conflict’.

The other prominent neutral states within Europe – Austria, Sweden, Finland and Ireland – had no such qualms about joining the UN, and all of them take a different approach to neutrality. As a young diplomat serving in Vienna (also a good while ago), I was frequently reminded of the demands of the Austrian State Treaty, the 1955 agreement with the four occupying powers (Soviet Union, UK, France and US) that bound Austria to not join any military alliances, and led to Austria declaring its permanent neutrality – while in the same year joining the UN. Austria affirmed it would follow a policy of “active neutrality”, offering its good offices for East-West issues. And now, Vienna has of course become the third home of the UN, after New York and Geneva.

In Sweden, the question of neutrality is quite a live issue at present, although not with respect to the UN. Sweden has long championed the UN and sees no problem with the country’s neutral status. Indeed, the most famous of all UN Secretary-Generals is perhaps Sweden’s Dag Hammarskjold. Sweden’s current debate revolves around a closer association with NATO, the Western military alliance with which the country already maintains a degree of cooperation. Membership of NATO, unlike the universal United Nations, would clearly put an end to neutrality, yet there are many voices in the country who would opt for NATO membership as a realistic policy in the current troubled geopolitical situation, as well as many others who would instead hew to neutrality.

Finland and Ireland are other European states which have elected for neutrality at one point or other in their national history and maintain this choice today. Like Sweden and Austria (and Cyprus and Malta, two other professedly neutral states), they are members of the UN, the EU, but not of NATO. And, these memberships do raise questions: Is it strictly neutral to go along with UN sanctions imposed against another state? Perhaps the ‘universal’ nature of the UN allows for such action without jeopardising neutrality, but what of the EU, with its growing initiatives under a Common Security and Defence Policy? At least Costa Rica and other neutrals beyond Europe have no such issues.

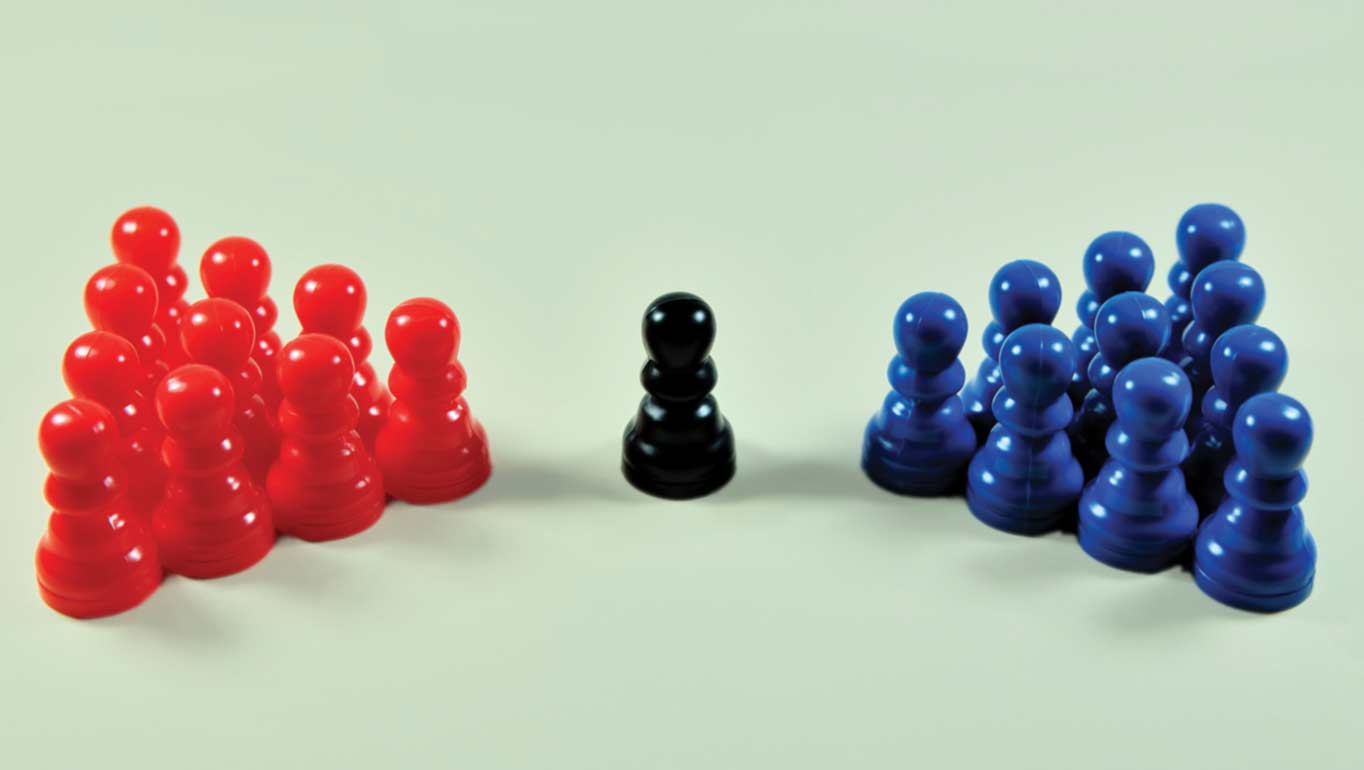

The first UN Secretary-General, Trygve Lie, declared that international organisations and neutrality were on two different planes. Now we have the UNGA encouraging respect for neutrality as an instrument of preventive diplomacy. Woodrow Wilson, bitterly frustrated by the US Congress’ refusal to join the League of Nations, dismissed armed neutrality as “ineffectual enough at best”, yet the international solidarity demonstrated by some of the core neutral countries – Sweden, Austria and Switzerland – has long been exemplary. Ultimately, this is all about politics, not international law. The debate over neutrality is linked to domestic political debates pitting isolationists against interventionists: a debate long current in the US and one that straddles party lines of left and right. And, when we debate humanitarian intervention and national sovereignty, we raise some of the same sets of issues. Moreover, in several historical occasions, for example during World War II, neutrality may have been more a question of survival than of free choice. How we view neutrality today depends on shifting political currents, on alliances changing with new conditions, on new threats and challenges in the face of which no one can remain ‘neutral’ – but this is far from the strictly political neutrality understood by that Resolution 75/170, where we began.