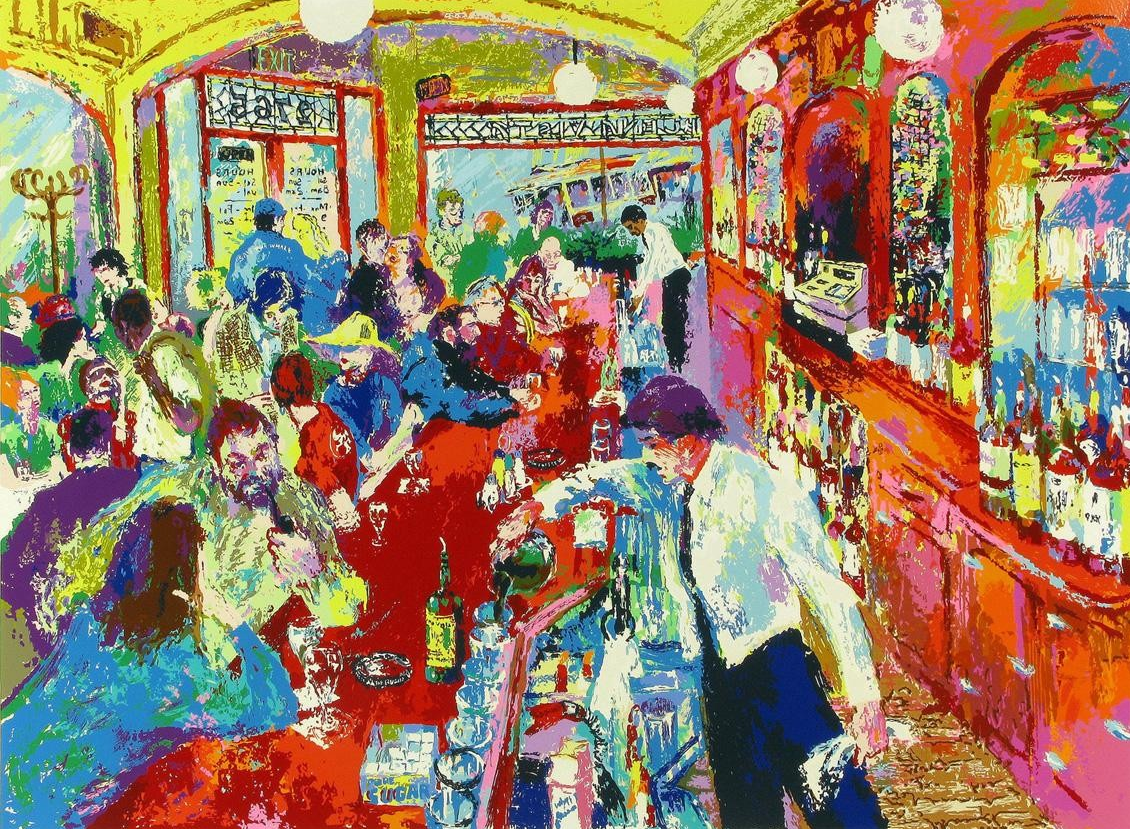

Vodka at a Polish Christmas, sherry with mince pies, a G&T at six, wine pairings (white with fish, red with meat), the festive blaze of brandy over Christmas pudding—drinking is woven into our life. Grabbing a “brewski” with friends, drinking a Piña Colada on the beach. Even religion reflects it: wine at celebrations and in scripture.

Did you know that in 1948, 82% of men and 41% of women in Britain smoked (including cigarettes, pipes, and cigars), rates similarly reflected worldwide. A study of 41,000 British physicians in 1951 found that 87.3% of them smoked tobacco in some shape or form.[1] Isn’t that unbelievably, incredibly high? Doesn’t seem like it could be true, but it is. The evidence linking smoking and cancer didn’t start appearing until 1950[2] and then it wasn’t until 1965 that TV ads were banned in the United Kingdom and not till 1971 that warnings began appearing on packets.

Just as in 1950, we are at the point where we have conducted large analyses of alcohol (in 2018) so that by January 2023, WHO was able to state categorically that no amount of alcohol is safe for health[3].

WHO’s position, echoed by The Lancet Public Health[4], overturns the once-popular idea that “a glass of red is good for you.” Why? Because earlier studies were muddied by confounding: wealthier, healthier people drank moderately; some “non-drinkers” had quit due to illness (“sick-quitter” bias). When you apply the controls properly, the protective halo disappears.

Just like the claim that a glass of red wine is good for you, in the 1940s there were claims that ‘For your digestion’s sake, smoke Camels’ – and even that smoking conferred throat protection and less irritation.

The reality is that alcohol is toxic, psychoactive, addictive and classified as a Group 1 carcinogen—the same category as tobacco, asbestos and radiation. It causes at least seven forms of cancer, including breast and bowel cancers. In fact it is accountable for 4.4% of cancers diagnosed globally.[5] Just recently, the University of Oxford, Yale University, and the University of Cambridge conducted the most comprehensive study of alcohol consumption and dementia risk to date with half a million participants[6]. It found a continuously increasing trend of higher dementia risk with greater alcohol intakes, suggesting that any level of alcohol consumption increases the risk of dementia, with no evidence that drinking alcohol may have a protective effect.

How does it work? In the body, alcohol is metabolized to acetaldehyde, which damages DNA. Although dose matters—more is obviously worse—risk starts above zero. Strikingly, in the WHO European Region, about half of alcohol-attributable cancers arise in people drinking at “light” to “moderate” levels (less than two bottles of wine, fewer than six pints of beer, or fewer than ten shots of hard liquor a week). That is actually very close to being within what the UK National Health Service (NHS) currently recommends as a maximum (no more than 14 units/week) and similar to current US guidelines. Even these recommended levels pose a significant risk. So much for protecting the public…

None of this requires sneering at custom. A communion sip is tiny and symbolic; many churches already use alcohol-free wine. The point is not to police sacraments, but to stop glamorizing routine drinking and to align commercial practice and public policy with what we now know. When the risk is dose-responsive and begins above zero, the default in everyday life—work socials, sports sponsorships, daytime TV—shouldn’t be to push alcohol as if it were harmless.

Globally, tobacco kills about 8 million people a year; alcohol kills about 3 million. Alcohol’s spillovers—violence, road injuries, domestic abuse, mental-health harms, and fetal disorders—are considerable. Economically, both impose costs that exceed the tax revenue they bring in; UK estimates put alcohol’s societal cost (around £21 billion) well above alcohol duty received (around £13 billion)[7].

On weekend nights, alcohol can account for up to 70% of Accident and Emergencies attendances. In 2023/24, alcohol was implicated in 1 million admissions (around 6% of all hospital admissions) in England, and it cost the NHS – which is chronically strapped for cash – a staggering £4.9 billion.

Here are some further somber statistics: alcohol doubles the risk of suicide, it is involved in 39% of violent incidents and around a third of murders, it is involved in higher levels of domestic abuse and sexual assault, higher public disorder, and to round it off, drunk driving led to around 260 deaths and 1,860 serious injuries in the UK in 2023.

We don’t need prohibition. This was tried in the US in the 1920s and early 30s and failed. We need the same approach that made smoking become a rare vice without criminalising smokers. Governments could raise taxes, adopt minimum prices per unit to curb cheap, high-strength products, and use licensing to limit both late-night availability and outlets open on every street corner. On marketing and sponsorship, they could phase out ads that reach children and teens—including sports sponsorships and influencer content—and end “alcohol everywhere” product placement in general-audience TV. Packaging and labelling should carry cancer warnings and standard drink/unit information on every container, with plain-pack elements for high-risk categories. In healthcare, they could train clinicians to routinely discuss alcohol including the risk of cancer with patients and expand support and treatment. Finally, we as a society need to shift our norms by making alcohol-free options the standard at work events and public venues and the government can run public campaigns that remind us that there is no safe level.

We can swap the ritual, not the moment. Trade the shot for flavour: try a ginger shot. Replace the wine with an alcohol-free option: sparkling water with lime or orange, a citrus spritz (half fresh juice, half soda water), hibiscus iced tea, or a herbal infusion. And as a society we don’t hydrate enough. Water should be the default, keeping sugary drinks occasional, and drinking tea/coffee in moderation.

Culture is not a museum. Christmas lights are LED now; pubs are smoke-free; cars have airbags. “Dry January” and the rise of good alcohol-free drinks show behavior can shift when cues and choices change. The science is now unequivocal and doing for alcohol what was done for tobacco will save lives, money, and misery. In 20 years’ time we’ll look back on these days as we look back to the days when most people smoked in the 1950s – as a time that was long overdue for a change. And all the while we can keep what matters most: the company. And we can still have mince pies and Christmas pudding!

[1] https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2085438/pdf/brmedj03396-0011.pdf

[2] Early smoking–cancer evidence (e.g., Doll & Hill, BMJ, 1950; Wynder & Graham, JAMA, 1950).

[3] WHO/Europe. “No level of alcohol consumption is safe for our health.” Policy brief & news release, Jan 2023.

[4] The Lancet Public Health commentary on low-level alcohol and cancer risk (aligning with WHO’s “no safe level”).

[5] https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/alcohol

[6] https://ebm.bmj.com/content/early/2025/09/16/bmjebm-2025-113913

[7] UK cost figures as per government and public-health estimates (e.g., HM Treasury/Public Health England)