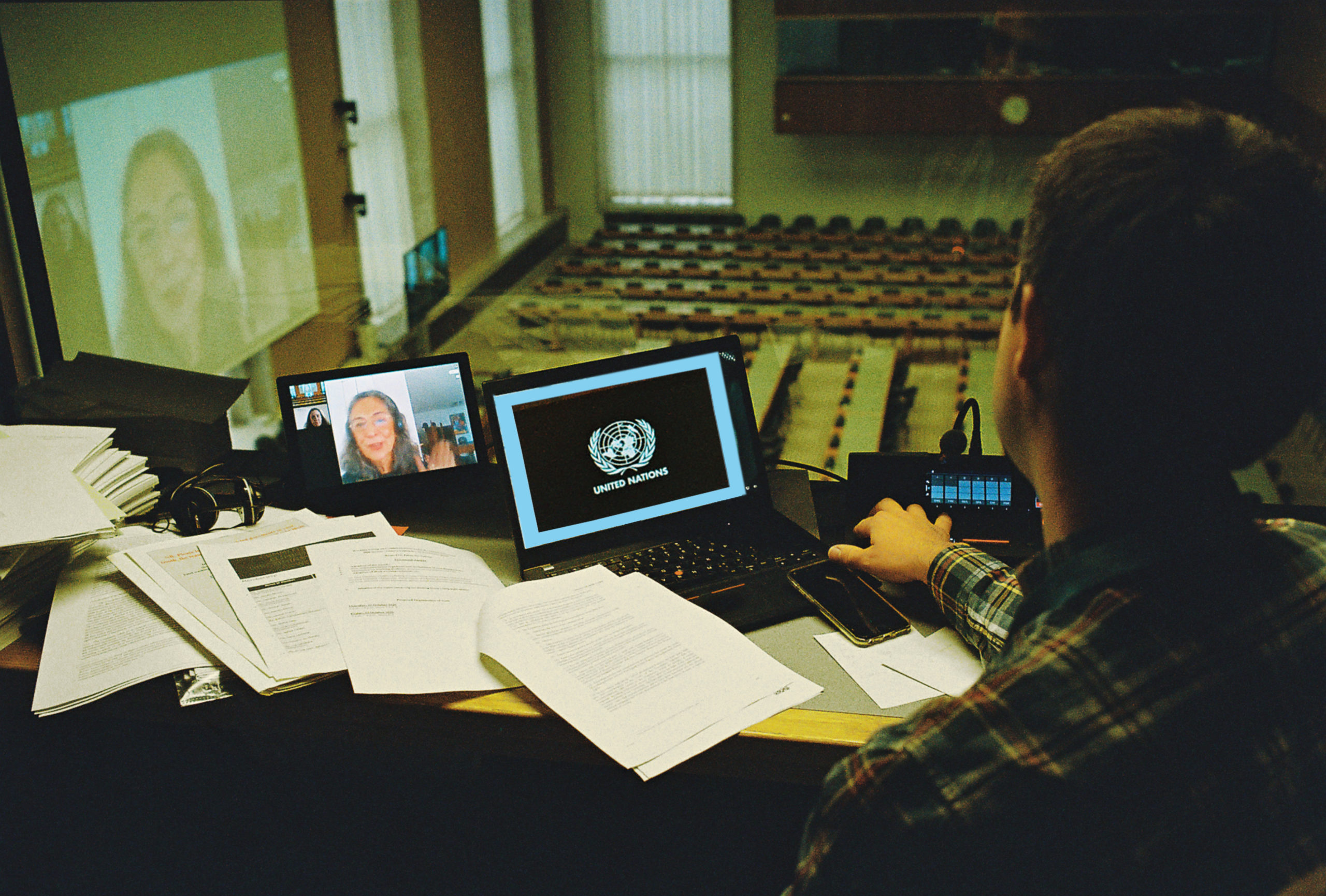

Teamwork is turning it into a success, but what do interpreters make of Remote Simultaneous Interpretation (RSI)?

Before the pandemic, interpreters’ experience of RSI was sporadic and invariably negative. It was often sprung on them unannounced and involved sound quality so sub-standard that it ruled out faithful performances. Participants rarely used the microphone they were recommended nor abided by the guidance they were given. Organisers tended to have unreasonable expectations and doubted the interpreters’ judgment on feasibility. And interpreters would systematically double as moderators-cum-sound technicians. Now that all meetings serviced by UNOG interpreters involve remote participation (RSI or WebEx), do they feel any differently about this technology that has turned up in their booths uninvited but effectively saved them from obsolescence?

“RSI has been hastily hailed as the new normal – but not by all Member States.”

Much as it would be wonderful to report that the sound quality is now reliably decent in every meeting with RSI, the fact is that it remains stubbornly unpredictable and wholly dependent on the infrastructure of the participant’s location. In the Palais des Nations, ICTS and the sound technicians have done a sterling job connecting the RSI platform to feed directly into the interpreting consoles of the rooms equipped with a Dante Interface (XVI, XVII, XIX, XX, Tempus 2 and, though it lacks cameras, the Assembly Hall).

They also regularly monitor the signal received and alter settings to optimise the sound heard by interpreters. However, they cannot make up for Wi-Fi outages and microphone malfunctions.

It would also be heartening to relate that remote participants have suddenly been imparted with healthy habits, such as securing a noise-cancelling (i.e. loop-preventing) headset with an integrated (or unidirectional, standalone) microphone; favouring an ethernet cable over Wi-Fi; closing the doors and windows of their office or living-room to prevent beeping cars, barking dogs and boisterous children from being overheard; adjusting their camera so that interpreters can read their lips rather than scrutinise their forehead; minimising the rustling of papers and the pings of cell phones; and muting or unmuting their microphone depending on whether they wish to hear or speak. Once again, sadly, none of these habits are yet second nature to even seasoned remote participants who continue to view them as optional.

“Moderators have become the answer to many interpreters’ unuttered prayers.”

This being said, whereas these vexations went unaddressed in the past, today they are tackled by a dedicated team of moderators recruited from the ranks of the sound operators (who are already versed in the art of microphone management) and other UNOG services on temporary cross-assignment (for whom the inner-workings of meetings are novel). Typically, they connect and carry out sound tests with each participant shortly before the start of every meeting with RSI; and remind them of the above-mentioned habits.

Throughout the meeting, they also keep a watchful eye on the status of their connection – asking participants to refresh their browsers if required; and discreetly assist the Chair in administering the list of speakers. A vigilant presence behind the scene, they are not afraid to step in and interrupt a meeting if they feel that communication has irretrievably broken down for a participant.

On a par with the technicians’ herculean wizardry, the appointment of two moderators per RSI meeting was possibly the best innovation prompted by the pandemic. In keeping the spotlight permanently focused on the need for technical requirements to be respected, they have significantly increased the interpretation-awareness of participants and organisers alike and thus become the answer to many interpreters’ unuttered prayers. But they are not a silver bullet. They can recommend and remind all they want but they have no power to compel. Whether they eventually succeed in inculcating healthy habits to remote participants – through constant diffident interruptions and polite reminders – remains to be seen.

In the meantime, notwithstanding the excellent offices of moderators and the best endeavours of sound technicians, interpreters are noticing that their hearing is suffering from them having to turn up the volume of their headsets in order to decipher the original (failing which the quality of their output would decline) – tantamount to straining to read texts printed in red against a green background all day long.

To be sure, they are as determined to discharge their duties as diligently as the conference officers – who are running twice as fast to supply documents to interpreters in single booths – and technicians – who are spending five times longer starting up a meeting room in the morning – but they cannot afford to sacrifice their most precious working tool in the process.

RSI has been hastily hailed as the new normal – but not by all Member States. To quote a member of the Conference on Disarmament speaking on the 27th of August 2020: Virtual formats and online exchanges do not yield the same outcomes as face-to-face meetings. Hybrid meetings have kept the work of the CD alive, but the experience has shown that they are not the best solution for our future work.