I had not planned to follow in James Baldwin’s footsteps over Easter. Neither had I planned to follow Teju Cole’s or Nativ’s path. But here I was walking amongst the weathered but resilient traditional houses of this spa village of Leukerbad in Switzerland looking for the house where Baldwin stayed some 70 years ago in 1952 where he completed his seminal autobiographical book ‘Go Tell it on the Mountain’

I had never heard of Leukerbad, apparently the highest alpine thermal spa in Europe, until I came across a 2014 article by author Teju Cole in the New Yorker where he sought to reread Baldwin’s essay ‘Stranger in the Village’ and cast his modern eyes on the place that inspired this piece of writing. That article, entitled “Black Body: Rereading James Baldwin’s “Stranger in the Village” was in itself a modern treatise on race.

All of us with any interest in race relations and good writing know James Baldwin. Even if you had never read one of his books you have likely heard one of his quotes. One of the strange things I’m most proud of is in 2013 suggesting a Baldwin quote to Pascal Lamy, then Director General of the Geneva based World Trade Organization to anchor his preface to the book “The History and Future of the World Trade Organization” when I worked there. Imagine that? A quote by a James Baldwin at the opening of a publication on multilateral trade! (The quote was: “History does not refer merely, or even principally, to the past. On the contrary, the great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are unconsciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is literally present in all that we do.”).

That said, I had no idea of Baldwin’s link to Switzerland even though I had lived here for 20 years. I dissected Cole’s essay before I decided to tackle Baldwin’s story of isolation, knotted anger, bitter resentment and exploration in his time in Leukerbad. During my research I also came across an article in German detailing Swiss musician and rapper Thierry Gnahoré’s (better known as Nativ) semi- pilgrimage to this little village. It seemed to me that black men, like Cole and Nativ were keen to juxtapose their experiences of today with Baldwin’s experiences of 1952. All three of these essays examined race and that feeling of otherness. Baldwin saw in his time here, a critical reveal of the state of the black man in America. His story begins almost like a travelogue and ends up being an indictment on race relations and social politics in his United States. Cole, a Nigerian- American, brought an even deeper analysis breaking down many of the inbuilt prejudices, and yes even ignorance, that Baldwin may have had regarding the achievements of his own race.

Baldwin’s reflection of the lineage of whites to the great composers and creators of the past always struck me as misplaced wonder, while also showing his lack of imagination for the creative arsenal of his ancestors- enslaved people from Africa- whose achievements would obviously not have found themselves in recorded history given that the recording of history is a subjective act often led by the oppressors. But both Baldwin and Cole were exploring their story from the perspective of being African-American. Even Nativ had a different dynamic being European born but of black heritage. What of those like me? From the Caribbean who like African-Americans are the children of the enslaved but unlike in the United States and in Europe we are essentially governed by people who look like us. We are majority black countries run and led by black people even if we have to make allowances that far too much of the economic wealth may be out of the reach of the majority. Would I have a similar reaction to Baldwin? Would I also feel like a stranger here?

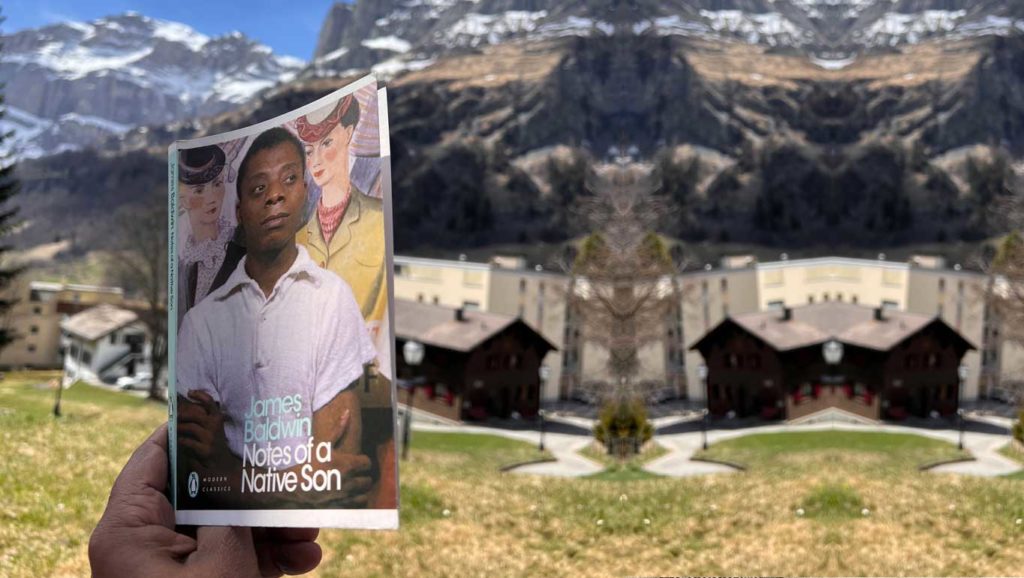

I was not the only person of color in the village. I saw a young couple and a lady around my age as soon as I stepped off the bus. We- as we always do in places like this- acknowledged each other with a nod and a smile. So already we were four times more people of color than Baldwin saw! I decided to read ‘Notes of a Native Son’, the collection that contains ‘Stranger in the Village’ in a crowded restaurant that first day I was there. I read two pages and put it down- face down. I felt both protected and cowardly cloaking my ‘otherness’ in the protection of the most famous person that had ever visited this village: a black man. I felt more powerful here knowing that Baldwin had come, stared the ignorance directly in its face and recorded it for all to see. I felt heard that in the town square stood a faded wooden panel cheaply but sympathetically put together with a printed out version of ‘Stranger in the Village’ contained therein. I felt that I had every right to be there because Baldwin had come before. I have not always felt that way in parts of Switzerland, Europe or the United States to be honest. Prejudice, especially micro-aggression, is an odorous thing: so hard to prove but so easy to feel.

‘Stranger in the Village’ the short story inspired by Baldwin’s time in Leukerbad. Credits: Matthew Wilson.

I saw many of the sites that Baldwin mentioned: the lone Catholic Church, the enigmatic Ballet Hall, even the remnant of the lone butcher’s shop that was here when he visited. However, Leukerbad also had hotels and restaurants at every corner, a number of grocery stores and those specialist boutiques that are so endemic to Switzerland: there is never anyone buying but yet they remain open season upon season. This was no longer Baldwin’s Leukerbad. But then I entered the thermal spa and was once again reminded of my otherness. I was the only person of color there for the whole day. It was jarring and it was a reminder of how spaces that may not be formally closed to us, can be closed in habit and practice. I swam in the outdoor pool under the mountains and the sun and I remembered reading those stories of ‘white only pools’ and swimming grounds being bleached and cleaned just because a black person dared to set foot in it. Again I was standing on the shoulders of those before me. The Baldwins and many more who stepped into those pools, or those schools, or sat on those buses, or took control of their governance. I swam without a care in the world because if there was a care- it wasn’t for me to carry that burden. When I left the spa hours later I saw two women of color checking in. We nodded at each other. As we do. Their nod asked ‘it’s ok? It’s a safe space?’ and my nod said ‘go in and swim until you are like a prune without a care in the world’.

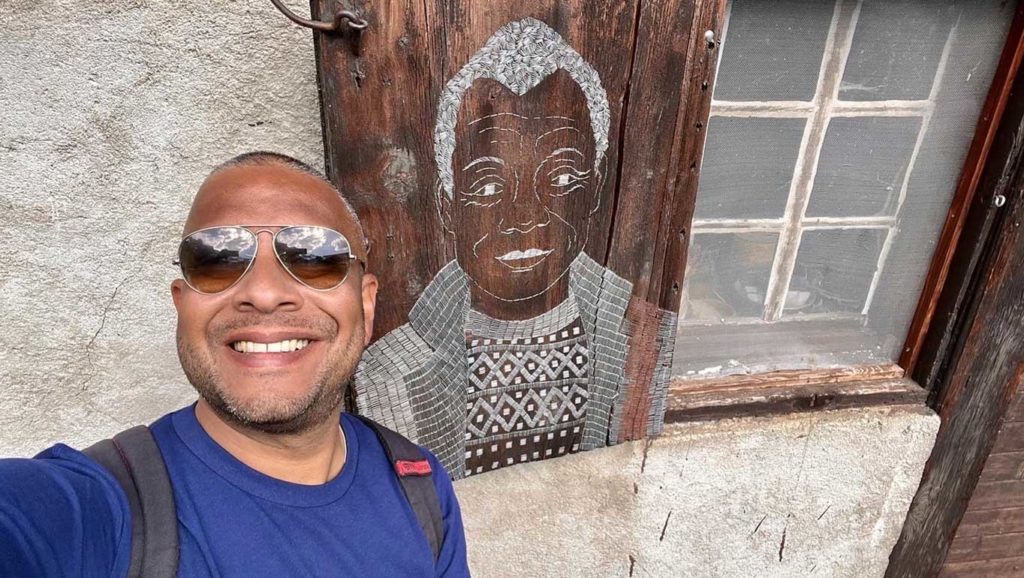

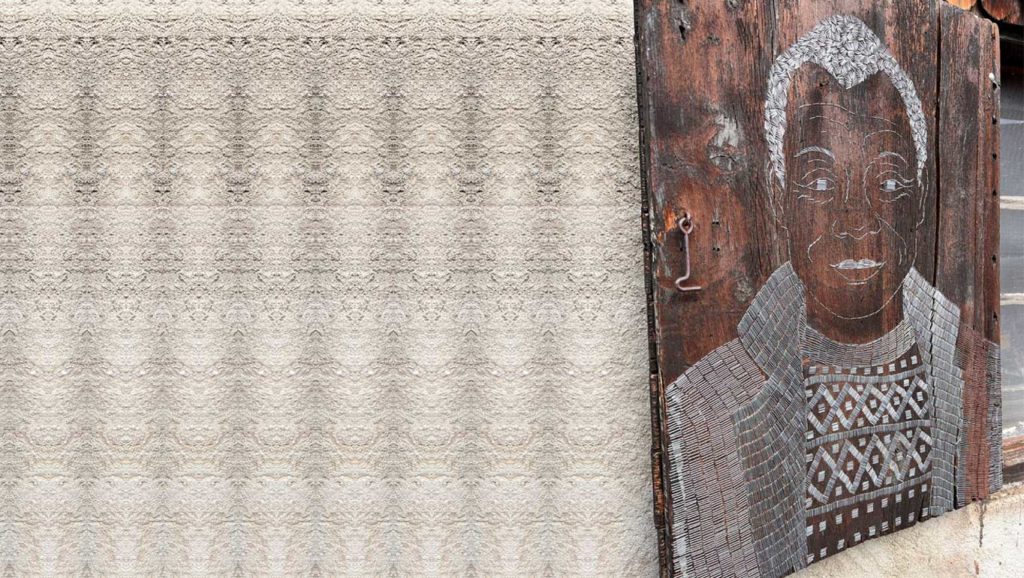

I also spent some time trying to find a memorial in art done to honor Baldwin by Haitian-American artist Sasha Huber. There were no signs, no directions online, no evidence that this piece of art was anything more than an urban legend. I searched up and down the little road where the vague mentions online suggested it could be. With the soundtrack of the music Baldwin listened to during his time here blaring in my ears (Bessie Smith) I still came up with nothing. Then something- is that you Baldwin?- led me up some steep creaky stairs into what seemed to be someone’s back yard. There it stood on the window of the house that he stayed in and which inspired ‘Stranger in the Village’, smiling and looking at the mountains in the distance. As I looked at this proud yet discrete piece of art all I could think is that this really was more than Baldwin could have imagined when he trudged through the snow filled streets of the village. Here forever emblazoned in metal staples was a piece of commemorative art by a Haitian-American woman being seen with fresh eyes by a black Barbadian man living in Switzerland. We are no longer strangers in the village. At least not in this village.