The world faces a growing sense of disillusionment, as inequality rises, trust in institutions falters and climate and ecological collapse accelerates. The United Nations Secretary-General has warned that the social contract is broken. The converging crises of climate, health, biodiversity loss, and economic precarity demand more than incremental reform. What is required is a deeper rethinking of the relationships among people, the planet, and power.

This new book Eco-Social Contracts for Sustainable and Just Futures responds directly to this moment. It introduces a framework of collective agreements that can restore trust, promote justice, and regenerate ecosystems by repositioning societies as social-ecological systems. Instead of treating prosperity as a race for bigger numbers, eco-social contracts imagine it as a garden we tend together—one that thrives on diversity, care, and reciprocity.

An eco-social contract can be understood as an implicit or explicit collective agreement across multiple levels of governance among individuals, communities, organisations and governments to redefine how people relate to each other, to nature and to power, so that well-being, fairness, and ecological regeneration become central. As highlighted in recent research on alternative economic visions, eco-social contracts constitute a transformative economic perspective, yet they go beyond economics by reshaping the underlying social, political and institutional arrangements through which societies organise change.

Former UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and Chair of The Elders Mary Robinson notes, “an eco-social contract must be built on structural justice, intergenerational equity and inclusive governance.” These new compacts recognize that our economies and societies are embedded within the biosphere, not separate from it. This understanding is deeply rooted in Indigenous cosmologies such as Ubuntu in Africa, the Andean vision of Buen Vivir or Sumak Kawsay in Latin America, and Eco-Swaraj movements in India that link ecological stewardship to self-governance and justice.

As one of the founders of Kalpavriksh, an Indian environmental NGO, Ashish Kothari reminds us, “Eco-swaraj is about radical ecological democracy—a system where communities govern themselves with respect for the limits and rights of nature, and where well-being is measured not by GDP, but by harmony with all life.”

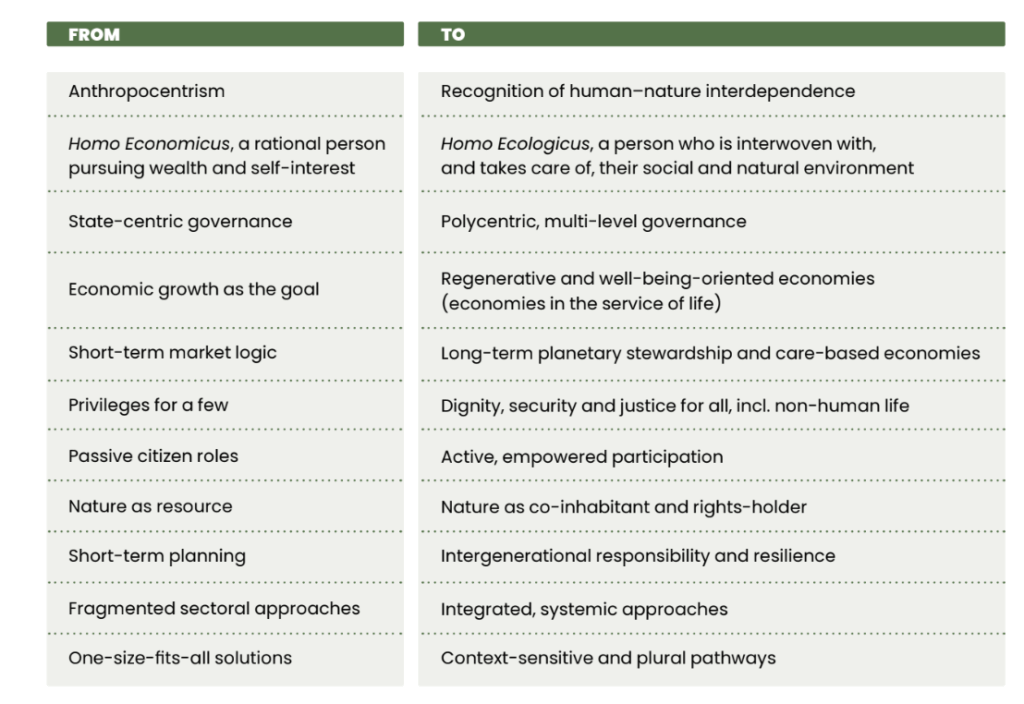

Feminist and care-based economies echo this ethos by valuing reciprocity, empathy and the invisible work that sustains life. As the table below illustrates, this shift from current to new eco-social contracts marks a profound paradigm change—from competition and extraction towards cooperation, care and regeneration. These principles are coming to life across the world. In New Zealand, the Whanganui River has been granted legal personhood, recognizing it as a living ancestor rather than a resource to be managed. Across the Americas, community-led climate justice initiatives in the United States and rights-of-nature reforms in countries such as Colombia and Bolivia also reflect emerging eco-social contracting. In Ecuador, the constitutional principle of Buen Vivir redefines development as living well in harmony with people and nature. In India, Eco-Swaraj communities practise local democracy and regenerative agriculture. In Kenya and Japan, eco-villages are testing low-carbon, community-driven models of prosperity. Local energy cooperatives in Germany and the Netherlands co-own renewable infrastructure, while food cooperatives co-manage farmland — ensuring that both energy and food production benefit local people rather than distant shareholders.

Citizens’ assemblies in France and Ireland are experimenting with new forms of participatory democracy, giving people a voice in shaping the transitions ahead. These examples show that the seeds of eco-social contracts are already being planted—and that new relationships between people, planet and power are possible. As UNEP’s Director Inger Andersen notes, “we need new social contracts that put nature and people at the heart of our economies.”

Eco-social contracting is also underway at broader scales. The Paris Agreement, the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework and the European Green Deal all embody emerging forms of eco-social compacts between nations and nature. Across sectors, movements from rights-of-nature to alternative economics and democratic climate governance demonstrate that societies are already reimagining their social contracts. Together these initiatives show that eco-social contracting is not abstract but part of a living transformation already unfolding worldwide.

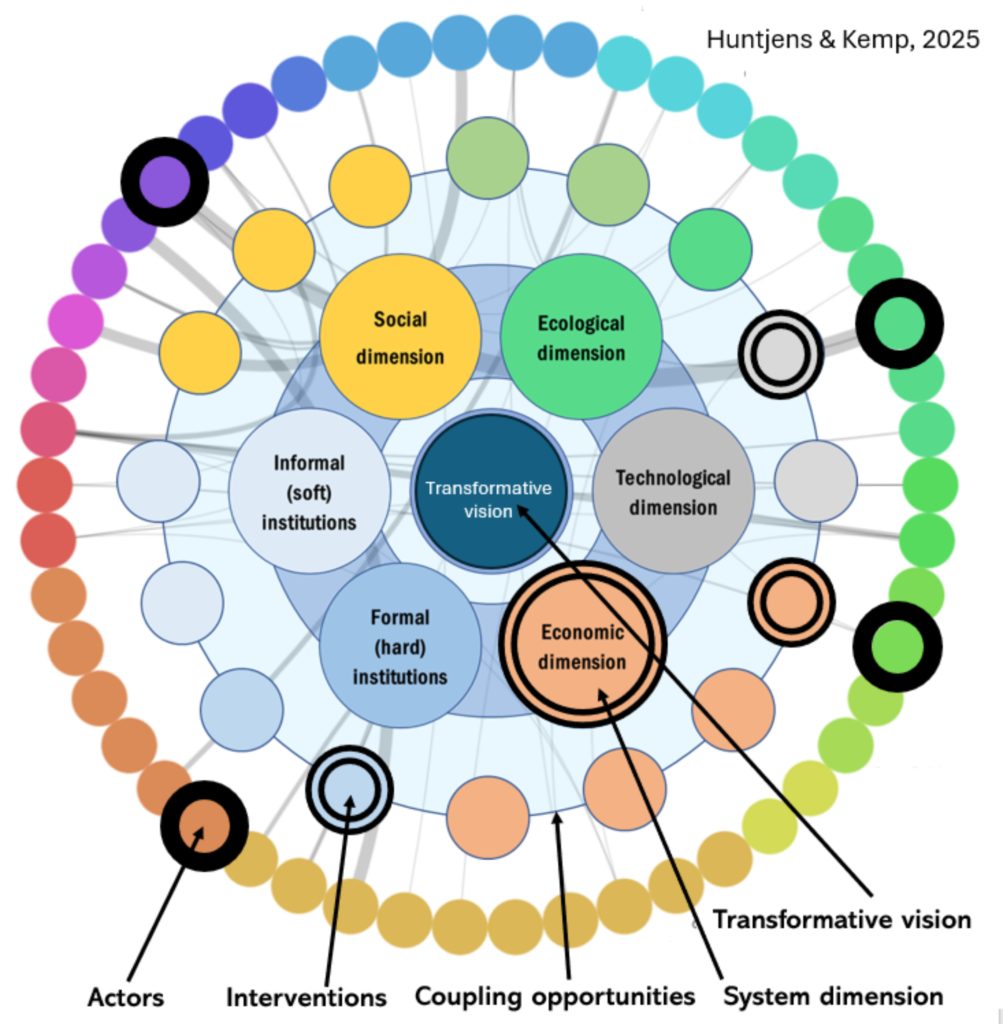

The “Transformation Flower Approach” is one practical way of putting eco-social contracting into action. It offers a structured but flexible method for guiding systemic change, showing how shifts in values, governance and daily practices must be woven together. Each “petal” represents a key dimension of transformation — social, ecological, economic, technical, and both formal and informal institutional arrangements. Together, these dimensions help actors identify where change is needed and how different pathways can reinforce one another. Rather than focusing on single solutions, the Flower helps people and organisations co-create pathways that align governance, culture, everyday practices and economic life with long-term social, ecological and economic wellbeing.

Some may wonder whether such a vision is realistic, yet transitions toward alternative economic models are already unfolding. Regenerative, wellbeing, post-growth and circular approaches are gaining ground across the world. The Wellbeing Economy Alliance has helped several countries including New Zealand, Scotland, Iceland, Wales and Bhutan adopt wellbeing as a guiding principle, while the Doughnut Economics model is inspiring cities such as Amsterdam, Brussels and Barcelona to design policies around social foundations and planetary boundaries. Similar movements are emerging in the Global South, where regenerative and solidarity-based initiatives from Buen Vivir policies in Latin America and Eco-Swaraj practices in India to community conservation and circular innovation across Africa demonstrate the growing momentum for systemic change.

Within this broader landscape, eco-social contracts are increasingly recognised in policy, research and practice as an alternative economic vision in their own right, one that reaches beyond the economic domain. They stand out by grounding economic renewal in the relational, social and institutional foundations that shape how societies organise change. Whereas many economic models focus primarily on reorienting goals, metrics or production systems, eco-social contracts translate shared values such as care, reciprocity, fairness and responsibility into concrete agreements about rights, duties and collective decision-making. Through their focus on inclusive and co-evolutionary governance, they provide the trust, legitimacy and institutional coherence needed for diverse economic alternatives to take root and endure. In this way, they do not compete with other visions but help bring them to life by embedding them in renewed relationships between people, power and nature.

Since UNRISD began calling for renewed social contracts a decade ago, and building on early academic foundations such as the Natural Social Contract framework, the vision and practice of new eco-social contracts are gaining recognition across international policy and science, from the UN Secretary-General’s Our Common

Agenda to recent UNESCO and UNEP initiatives and major assessments by the ILO, WHO and IPBES. Together these initiatives show that eco-social contracts are not abstract ideals but practical levers for rebuilding trust, inclusion and sustainability. They make trade-offs explicit and negotiable, clarify rights and responsibilities and help design transitions that are just from the start. As the Director of UNRISD Magdalena Sepúlveda Carmona observes, “a fair social contract must address the care economy and recognize that unpaid work sustains both people and the planet.”

The challenges of the twenty-first century cannot be solved by tweaking the status quo. As Kumi Naidoo puts it, “we must transition from systems that devalue life to economies that cherish sustainable well-being and shared prosperity.” They require a fundamental shift in how we see ourselves: not above nature, but as part of it; not consumers, but caretakers. Eco-social contracts provide the language and structure for this shift, while the “Transformation Flower” offers a method for turning it into action. Together they help reweave the bonds between people, planet and power, and open pathways toward just and sustainable futures.

Special thanks to Najma Mohamed and Manisha Desai for their assistance with this article.